MAIN GALLERY

Labor of Fire

THE DC ARTS CENTER’S CURATORIAL INITIATIVE PRESENTS

Curated By Benedetta Castrioto

Mentored by Jeffry Cudlin

Featuring janet e. dandridge, Fanni Somogyi, and Isabella Whitfield

FEB. 16 - MAR. 17, 2024

MAIN GALLERY

THE DC ARTS CENTER’S CURATORIAL INITIATIVE PRESENTS

Labor of Fire

Curated By Benedetta Castrioto

Mentored by Jeffry Cudlin

Featuring janet e. dandridge, Fanni Somogyi, Isabella Whitfield

FEB. 16 - MAR. 17, 2024

As part of the DC Arts Center Curatorial initiative, curator Benedetta Castrioto presents Labor of Fire, an exhibition about the economics and the politics of the art world, featuring sculpture, multimedia installations, performance, and time-based media. The selected artists, janet e. dandridge, Fanni Somogyi and Isabella Whitfield, turn their artistic labor into a subject of inquiry as well as its means. Tracing within the art object the stories and processes of its own production, they recast the work of art as a fossil of labor itself. Faced with this collection of practices and works, visitors are invited to reflect on meditation, manual and administrative work, maintenance, care and craft as equally important and connected forms of worldmaking—thoughtful, directed action with the power to shape our social structure.

Featured Above

Fanni Somogyi

Precariously Placed, 2023

25” x 12” x 24”

Beams, plexiglass,

dust collected through sweeping in studio space

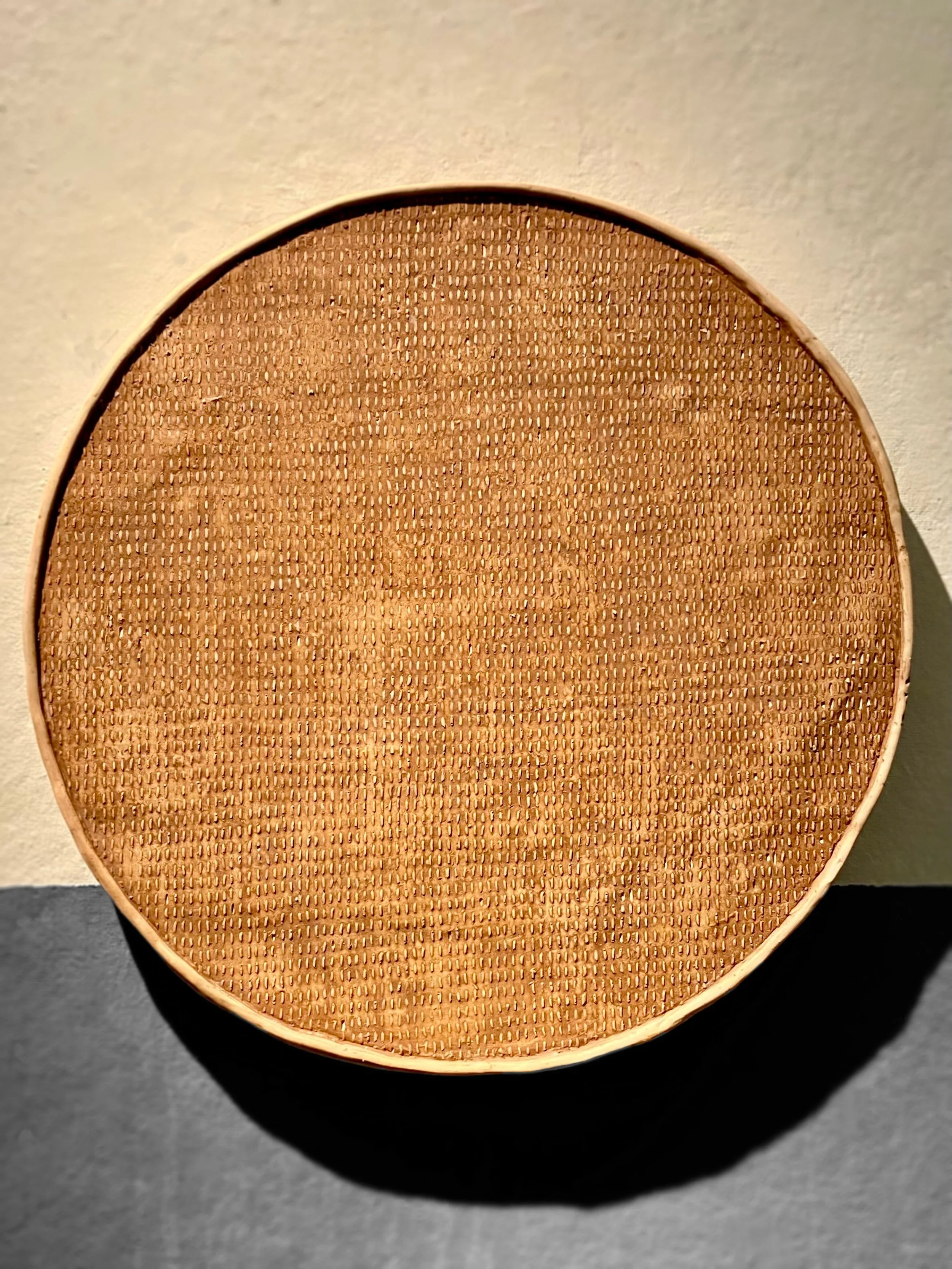

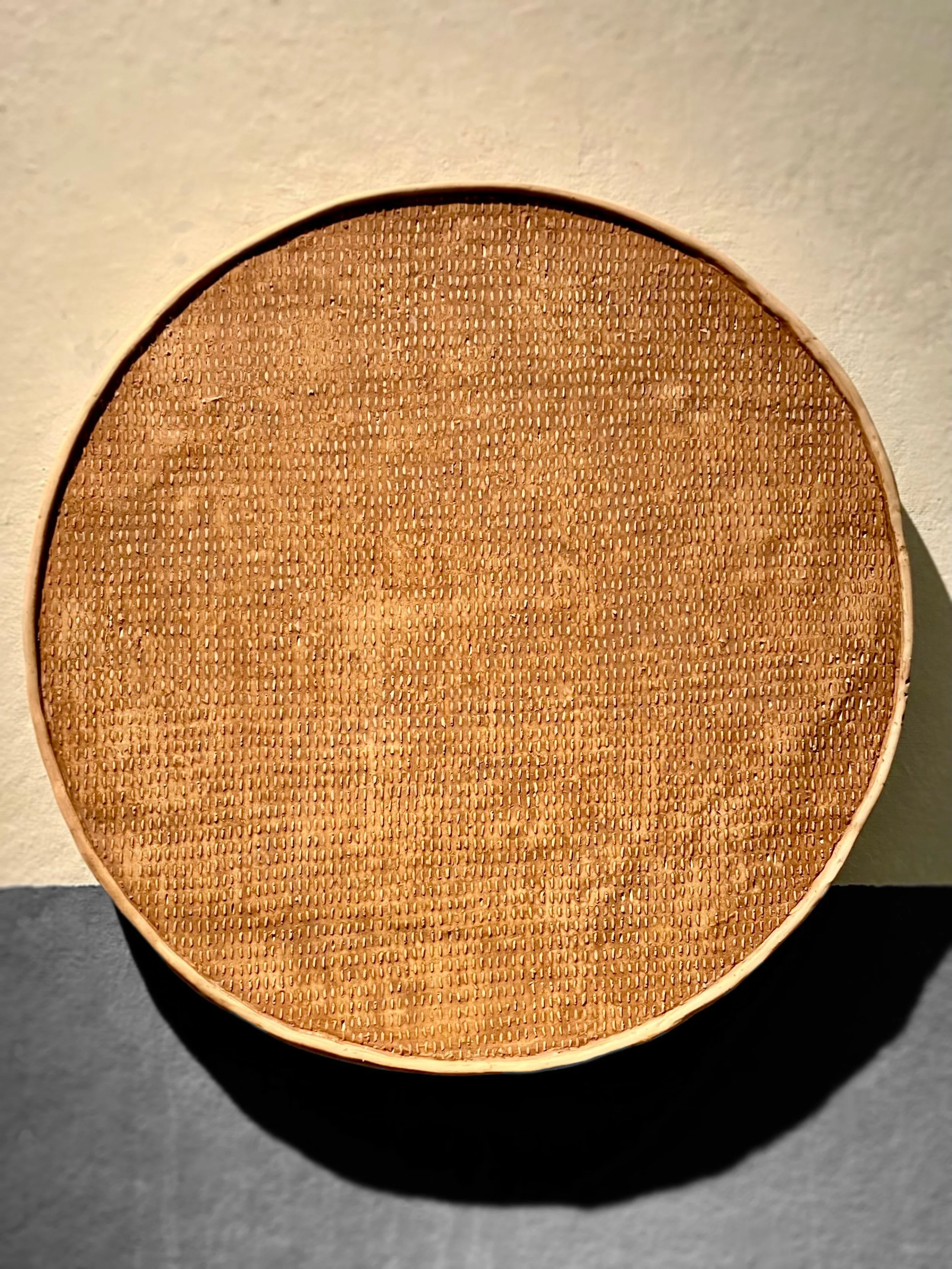

Featured Below

Isabella Whitfield

All in a day’s work

Performance with rice and pine table

ABOUT THE EXHIBITION

ABOUT THE EXHIBITION

As part of the DC Arts Center Curatorial initiative, curator Benedetta Castrioto presents Labor of Fire, an exhibition about the economics and the politics of the art world, featuring sculpture, multimedia installations, performance, and time-based media. The selected artists, janet e. dandridge, Julia Kwon, Fanni Somogyi and Isabella Whitfield, turn their artistic labor into a subject of inquiry as well as its means. Tracing within the art object the stories and processes of its own production, they recast the work of art as a fossil of labor itself. Faced with this collection of practices and works, visitors are invited to reflect on meditation, manual and administrative work, maintenance, care and craft as equally important and connected forms of worldmaking—thoughtful, directed action with the power to shape our social structure.

Featured Above

Fanni Somogyi

Precariously Placed, 2023

25” x 12” x 24”

Beams, plexiglass,

dust collected through sweeping in studio space

Featured Below

Isabella Whitfield

All in a day’s work

Performance with rice and pine table

Opening Celebration

Friday, Feb. 16, 2024

7:00 PM

Artist Performance - Live!

Saturday, Feb. 24, 2024

12:00 PM - 7:00 PM

Virtual Artist Talk

Saturday, Mar. 9, 2024

2:00 PM

Closing Reception

Sunday, Mar. 17, 2024

6:00 PM

EVENTS

EVENTS

Opening Celebration

Friday, Feb. 16, 2024

7:00 PM

Artist Performance

Isabella Whitfield

Sunday, Feb. 25, 2024

12:00 PM - 7:00 PM

Virtual Artist Talk

Saturday, Mar. 9, 2024

2:00 PM

Closing Reception

Sunday, Mar. 17, 2024

6:00 PM

Labor of Fire is an exhibition about the politics of work and economics in the art world. The project began as a critical reflection on institutional practices of artist engagement and broadened into an inquiry into the social and private spheres of artistic labor in neoliberal societies. Artists (together with a number of workers that rapidly grew between 1950 and 2010) have responded to the transition to a post-industrial service economy with increasing professionalization and academic institutionalization. They have become progressively more interested in theoretical discourse and in addressing, intellectually and emotionally, some of the most pressing cultural and political issues of our society. Yet artistic work is often economically precarious, exploited, and devalued—conditions with deep-running implications for various aspects of equity, including diversity and representation within the art world.

The exhibition puts labor in front of the audience to dispel the illusion that the gallery space can exclude or suspend the tension between art and equity. The artists in the show turn their own labor into a subject of inquiry as well as its means. By analyzing the creative process and including its least glamorous sides, they reframe discounted forms of labor, such as maintenance and childcare, as foundational. By tracing within the art object the stories and processes of its own production, they recast the work of art as a fossil of labor itself. Together, these works challenge institutions and art administrators to think about what fair support for artists is.

Labor of Fire also seeks to highlight the interdependence between intimate, private experiences of laboring and collectively shared ones. Meditation, manual and administrative work, maintenance, care, and craft coexist here as equally important and complementary practices of worldmaking—of building and tending to our social and physical habitats.

The title Labor of Fire is borrowed from Bruno Gullì’s 2005 book on the essential nature of labor. Gullì presents labor as a constitutive aspect of human existence. It is fundamentally thoughtful and directed action, he argues, a creative force that shapes our material and social environment. The economic paradigm of our society, capitalism, may categorize labor as productive or unproductive and value or reward it accordingly. But these categories are only the product of norms and conventions, geographic and historical circumstances. Labor that is unconcerned with ideas of productivity is “labor of fire.”

Contemporary artists live out the paradoxical struggle to practice this labor, moved by a creative, not an economic imperative. Many have opposed the objectification and commodification of their work, developing practices that challenge social expectations and norms of taste. Beginning with the Dadaists and their critique of art itself, this trend continued to evolve well into the 21st century, seeing the proliferation of a wide range of movements and expressive forms as varied as performances, happenings, environmental, social, and research-based practices. Most contemporary institutions accept—in fact, celebrate—the claim for artistic labor’s intellectual autonomy even as they try to capture and institutionalize ex-post some of the most anti-institutionalist practices, such as art strikes. A good example is the exhibition Messing with MoMA (2015), organized by the Library of the Museum of Modern Art in New York to showcase a history of controversies the organization was embroiled in, including, among others, the Art Workers Coalition’s 1969 Artists strike and Occupy MoMA (2012).

What is more, though, many institutional actors have come to use the idea of autonomy as a smokescreen that hides the power dynamics pushing artists into a condition of economic precariousness. Society construes the making of art as labor only ambiguously: At once personal vocation and social good, artistic labor is often exploited behind a rhetoric of entrepreneurialism. Capital and institutions absorb the fruits of the artist’s work, and the struggle for self-subsistence is the artist’s private matter.

The research underpinning Labor of Fire shows that this inquiry has a long history, dating back to at least the 1960s, with the formation of the Art Workers Coalition (1969) and continuing more recently with the work of organizations such as W.A.G.E — Working Artists in the Greater Economy (founded in 2008) — and the collective BFAMFAPHD (formed in 2012). Yet, institutions often still struggle to acknowledge and address the political economy of their operations. The development of AI technology to generate content through the massive harvesting of original work, to which it gives no credit, let alone remuneration, is a clear indicator that the tendency to separate human labor and experience from the work of art is alive and well. But this tendency continues to exist also in low-tech and institutionally dressed-up versions. Organizations (and their administrators) that believe seriously in the value of art must also seriously value the work that goes into making it.

This exhibition would not have been possible without the labor of many. My gratitude goes to the artists: janet e. dandridge, Julia Kwon, Fanni Somogyi, and Isabella Whitfield. Their labor—visible and invisible—is the why and the how of this project. I wish to thank The DC Arts Center team for their work in helping me bring this show to fruition and for being open to this reflection — holding not just physical space but also space for dialogue on equitable institutional practices. Last but not least, I am grateful for the support of Mentor Curator Jeffry Cudlin, who showed me through active advocacy that curating goes beyond planning exhibitions and displaying art, and fellow Apprentice Curator FAITH, who was throughout this journey a thoughtful sounding board and caring companion.

FROM THE CURATOR

FROM THE CURATOR

Labor of Fire is an exhibition about the politics of work and economics in the art world. The project began as a critical reflection on institutional practices of artist engagement and broadened into an inquiry into the social and private spheres of artistic labor in neoliberal societies. Artists (together with a number of workers that rapidly grew between 1950 and 2010) have responded to the transition to a post-industrial service economy with increasing professionalization and academic institutionalization. They have become progressively more interested in theoretical discourse and in addressing, intellectually and emotionally, some of the most pressing cultural and political issues of our society. Yet artistic work is often economically precarious, exploited, and devalued—conditions with deep-running implications for various aspects of equity, including diversity and representation within the art world.

The exhibition puts labor in front of the audience to dispel the illusion that the gallery space can exclude or suspend the tension between art and equity. The artists in the show turn their own labor into a subject of inquiry as well as its means. By analyzing the creative process and including its least glamorous sides, they reframe discounted forms of labor, such as maintenance and childcare, as foundational. By tracing within the art object the stories and processes of its own production, they recast the work of art as a fossil of labor itself. Together, these works challenge institutions and art administrators to think about what fair support for artists is.

Labor of Fire also seeks to highlight the interdependence between intimate, private experiences of laboring and collectively shared ones. Meditation, manual and administrative work, maintenance, care, and craft coexist here as equally important and complementary practices of worldmaking—of building and tending to our social and physical habitats.

The title Labor of Fire is borrowed from Bruno Gullì’s 2005 book on the essential nature of labor. Gullì presents labor as a constitutive aspect of human existence. It is fundamentally thoughtful and directed action, he argues, a creative force that shapes our material and social environment. The economic paradigm of our society, capitalism, may categorize labor as productive or unproductive and value or reward it accordingly. But these categories are only the product of norms and conventions, geographic and historical circumstances. Labor that is unconcerned with ideas of productivity is “labor of fire.”

Contemporary artists live out the paradoxical struggle to practice this labor, moved by a creative, not an economic imperative. Many have opposed the objectification and commodification of their work, developing practices that challenge social expectations and norms of taste. Beginning with the Dadaists and their critique of art itself, this trend continued to evolve well into the 21st century, seeing the proliferation of a wide range of movements and expressive forms as varied as performances, happenings, environmental, social, and research-based practices. Most contemporary institutions accept—in fact, celebrate—the claim for artistic labor’s intellectual autonomy even as they try to capture and institutionalize ex-post some of the most anti-institutionalist practices, such as art strikes. A good example is the exhibition Messing with MoMA (2015), organized by the Library of the Museum of Modern Art in New York to showcase a history of controversies the organization was embroiled in, including, among others, the Art Workers Coalition’s 1969 Artists strike and Occupy MoMA (2012).

What is more, though, many institutional actors have come to use the idea of autonomy as a smokescreen that hides the power dynamics pushing artists into a condition of economic precariousness. Society construes the making of art as labor only ambiguously: At once personal vocation and social good, artistic labor is often exploited behind a rhetoric of entrepreneurialism. Capital and institutions absorb the fruits of the artist’s work, and the struggle for self-subsistence is the artist’s private matter.

The research underpinning Labor of Fire shows that this inquiry has a long history, dating back to at least the 1960s, with the formation of the Art Workers Coalition (1969) and continuing more recently with the work of organizations such as W.A.G.E — Working Artists in the Greater Economy (founded in 2008) — and the collective BFAMFAPHD (formed in 2012). Yet, institutions often still struggle to acknowledge and address the political economy of their operations. The development of AI technology to generate content through the massive harvesting of original work, to which it gives no credit, let alone remuneration, is a clear indicator that the tendency to separate human labor and experience from the work of art is alive and well. But this tendency continues to exist also in low-tech and institutionally dressed-up versions. Organizations (and their administrators) that believe seriously in the value of art must also seriously value the work that goes into making it.

This exhibition would not have been possible without the labor of many. My gratitude goes to the artists: janet e. dandridge, Julia Kwon, Fanni Somogyi, and Isabella Whitfield. Their labor—visible and invisible—is the why and the how of this project. I wish to thank The DC Arts Center team for their work in helping me bring this show to fruition and for being open to this reflection — holding not just physical space but also space for dialogue on equitable institutional practices. Last but not least, I am grateful for the support of Mentor Curator Jeffry Cudlin, who showed me through active advocacy that curating goes beyond planning exhibitions and displaying art, and fellow Apprentice Curator FAITH, who was throughout this journey a thoughtful sounding board and caring companion.

Meet the Curator & Artists

Benedetta Castrioto, janet e. dandridge,

Fanni Somogyi, Isabella Whitfield

ABOUT THE CURATOR: BENEDETTA CASTRIOTO

Benedetta Castrioto is a curator and project manager with a passion for multidisciplinary projects. Interested in institutional and social critique, her research and work have been concerned with artistic and cultural production as praxis. In particular, she focuses on the intersection between social and environmental justice, and their incorporation in institutional practice and artistic process.

She was previously the program manager for Zoma Museum in Addis Ababa, and has worked with organizations in Ethiopia, Italy, Turkey, and the UK as an advisor on public programs and the execution of site-specific works.

She holds an M.A. in Arts and Cultural Enterprise from Central Saint Martins and an M.Sc. in Environment and Development from the London School of Economics.

ABOUT THE ARTIST: janet e. dandridge

Mother, Interdisciplinary Artivist, Arts & Activism Educator and Consultant, Liberator, Listener, Empathy Sustainer.

In her artworks, janet intersplices theatrical performance, photography, empirical data, identity politics, and whimsy into a keen reflection on social constructs. Primarily using performance art, interactive installations, and abstract photography, janet explores trauma, resilience, empathy, and the power of Black women. Spirituality, the personal empirical, and collective actions are key components that guide janet in her creations.

In 2017, janet formed fluidity, an art-centered educational experience that guides the public in artistic development of collaborative projects that positively affect social and political change. To participants, janet poses the question, “What are you actively doing to activate space as an Activist; as an Artist; as an Advocate?” Since 2013, she has been a volunteer consultant and organizer for the Black Coalition Fighting Back Serial Murders, a Los Angeles grassroots organization drawing attention to the serial murders of black women and girls in South Los Angeles. At present, the Coalition is working to build a permanent memorial to honor the victims and provide the families and South Los Angeles community with a “dignified space for reflection and healing.” For more information and to donate to the memorial fund, please visit https://rosesouthla.org/.

janet is a 2023 Arts and Humanities Fellow for the District of Columbia Commission on the Arts & Humanities. janet earned her Master of Fine Arts from Otis College of Art and Design in Los Angeles. She exhibits, performs, and teaches nationally and internationally.

ABOUT THE ARTIST: FANNI SOMOGYI

Fanni Somogyi is an emerging artist (b. Budapest, Hungary) currently working in Detroit, Michigan. She creates metal and plant assemblages with steel, aluminum, and, at times, plants that explore environmental kinship, disconnectedness, and care. Somogyi completed an MA in Curatorial Studies at the Node Center in Berlin in 2023 and earned her BFA from the Maryland Institute College of Art in Interdisciplinary Sculpture and Creative Writing in 2019. Her work has appeared in group shows, including “Sticky Entanglements” at Transformer DC, “YOU EFF OOH” at Maryland Art Place, and “Wild/Mild” at Vox Populi, among others. Somogyi’s sculptures range in scale from tabletop pieces to large-scale installations, including a public sculpture at the Franconia Sculpture Park (Shafer, MN), and the traveling art installation Pop Sheep at Olala Street Festival (Linz, Austria) in 2018 and at Sziget Music Festival (Budapest, Hungary) between 2015 - 2017. Research and writing are also crucial elements of Somogyi’s practice. She has written for BmoreArt Magazine, and her science fiction short story, “Galamb & Tinka,” was published in Perennial Press’ Supra Natural Anthology in 2019. Somogyi is currently pursuing an M.F.A. at Cranbrook Academy of Art.

ABOUT THE ARTIST: ISABELLA WHITFIELD

Isabella Whitfield is a multidisciplinary artist based in the DMV. After graduating from the University of Virginia, she spent a post-graduate year as an Aunspaugh Art Fellow. Whitfield has recently exhibited with the Hamiltonian Gallery, the Robert C. Williams Museum, the Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Museum, and the 1708 Gallery, among others. Residences include Penland, Anderson Ranch, Ox-Bow, Pyramid Atlantic, and VisArts Richmond. She is currently based in DC as a Hamiltonian Artists Fellow and is a Papermaking Associate at Pyramid Atlantic.